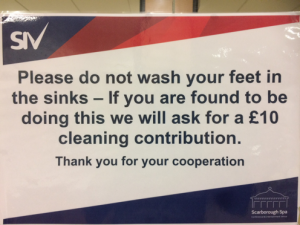

The 8th biennial Palliative Care Conference, held 2-3 November 2017 and organised in partnership by Saint Catherine’s Hospice and Hull York Medical School, met on a very wet morning at The Spa Conference Centre in Scarborough. If you had somehow missed the fact that you were on the seafront (there was water coming from all directions, after all), your suspicions would have been confirmed on the arrival to the bathroom. There are not many places that require a sign asking you to not wash your feet in the sink!

When people think of palliative care, particularly medical students at the start of their degree and members of the public, most of them will picture someone dying in a hospice after a long and hard journey with cancer. Whilst this is certainly part of what palliative care does, there are other areas of medicine where patients can benefit greatly from palliative care. Some of these areas were discussed at the conference and include delirium, young adults, frailty, dementia, and heart failure. However, I am going to focus on two themes from the conference that I found most interesting: responding to change and evidence within the field of palliative care, and an excellent workshop on conversations about sex and intimacy.

When people think of palliative care, particularly medical students at the start of their degree and members of the public, most of them will picture someone dying in a hospice after a long and hard journey with cancer. Whilst this is certainly part of what palliative care does, there are other areas of medicine where patients can benefit greatly from palliative care. Some of these areas were discussed at the conference and include delirium, young adults, frailty, dementia, and heart failure. However, I am going to focus on two themes from the conference that I found most interesting: responding to change and evidence within the field of palliative care, and an excellent workshop on conversations about sex and intimacy.

Evidence-based palliative care

The conference began with a thought-provoking keynote address from Professor Simon Noble, Clinical Professor in Palliative Medicine at Cardiff University and Honorary Consultant at the Royal Gwent Hospital. Professor Noble is extremely successful in the academic field of Palliative Medicine and has published over 200 original papers and conference abstracts, 20 book chapters, and 6 books. He explained that palliative care is a relatively new speciality, born of ‘radicals’ who suggested an approach to the care of the dying which challenged modern thinking and paved the way to the modern hospice environment. He went on to suggest that in its immaturity, palliative care has become ‘blinkered’ in to doing the same things they have always done and that they are not very receptive to change. He strongly encouraged us to step out of our comfort zones in the following two days and explore what is new and changing within the speciality, and to move from being ‘blinkered’ to being ‘brave’ – to change, not for the sake of change, but because it needs to be done.

The first day concluded with Professor Miriam Johnson, our very own Professor of Palliative Medicine and Director of the Wolfson Palliative Care Research Centre at Hull York Medical School, reminding us that palliative care is an evidence-based practice and we should ‘take off the blinkers’ when the data changes. She explored common myths from over the years that we now know to be incorrect from emerging evidence within palliative care.

Conversations about sex and intimacy

The most interesting part of the conference for me was attending a workshop on “conversations about sex and intimacy”. The reason I chose this is because throughout medical school, like many of my peers, I have always found sexual histories and intimate conversations to be challenging. I feared stumbling over my words and unintentionally making assumptions, and combining that with someone who is dying filled me with great anxiety. I went in with questions such as: How important is sex and intimacy to someone who is dying? How, when, and why would I need to discuss that with someone who is dying? How will knowing this make me a better doctor?

The workshop was led by Bridget Taylor, Advanced Nurse Practitioner in Community Palliative Care from Oxford. Bridget explained that she came to realise conversations about sex and intimacy are extremely important for all palliative care patients. She started off by sharing a story of a young, married woman with Multiple Sclerosis (MS) whom she cared for in the community. This lady required an indwelling catheter due to her disease, and nursing staff were frequently called to her home to replace it when it came out. One day Bridget was on her way to the patient’s house and started to wonder why she needed the catheter replacing so frequently. Was she having bladder spasms that expelled the catheter? Did she need something prescribing to reduce that? On reflection Bridget realised that this was a very medical approach and she did not look at this patient holistically.

When Bridget arrived at the patient’s address, she was greeted by the husband who led her up to the bedroom to see his wife. Bridget said it was in that moment that she suddenly viewed the lady as a married, sexual human being and not a disabled lady with MS. She realised that the catheters were being removed prior to the couple being intimate, then a nurse had to be called to insert a new one. Did that mean they could only have sex during the day time when they knew a nurse would be available to visit? Could they not have sex more than once in day? Bridget suddenly realised that this couple’s intimacy was being determined by the availability of healthcare. She subsequently taught the woman’s husband how to reinsert a catheter so that they did not have to rely on health professionals.

This case sparked Bridget’s interest in exploring the topic further: she went on to do a PhD in the area and met many more people with similar experiences. Bridget used further examples throughout the workshop and case studies for us to explore together. She encouraged us to work in small groups and devise ways to ask about how a patient’s illness impacts their sex and intimacy needs, whether they have a partner or are single. Many attendees had unintentionally overlooked the needs of those who are single, and incorrectly assumed that because they are dying and do not have a partner, it must not be important to them. I came away from the workshop feeling like my mind had been opened to an interesting area of palliative care I had not even considered before. I feel I now have a lot more insight into the intimacy issues that patients and their partners might be suffering with silently, and sensitive ways to ask about them. I hope that I will be able to carry this through to my future practice as a doctor and make sure to consider each patient fully and holistically.

Overall, the entire conference was extremely eye-opening and thoroughly enjoyable. I would recommend anyone with an interest in palliative care to attend the next conference.

Sarah Eccles is a HYMS graduate from 2018 and an FY1 doctor in Hull. She hopes to go into General Practice with a special interest in Palliative Care. In her spare time she enjoys playing board games with her friends and having lots of cuddles with her two adopted senior cats.

Sarah Eccles is a HYMS graduate from 2018 and an FY1 doctor in Hull. She hopes to go into General Practice with a special interest in Palliative Care. In her spare time she enjoys playing board games with her friends and having lots of cuddles with her two adopted senior cats.